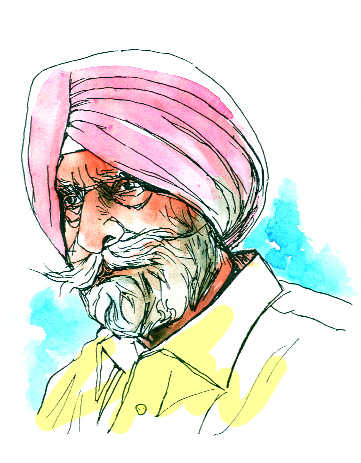

When on Friday afternoon we learnt of KPS Gill’s demise, my colleagues immediately contacted very many of his former colleagues with a request for an assessment of this man, who alone answered to the “supercop” moniker. A few agreed but quite a few declined, politely but clearly. It appeared that his detractors outnumbered his admirers.

That is not surprising.

After all, “KPS” represented a recurring dilemma of our times: an ugly mess gets created because the politicians and diplomats fail to do their job of reconciliation and resolution of conflicting claims and demands. Minor lapses and failures are allowed to pile up, curdling up into a stalemate, as forces of intolerance and instruments of violence get unleashed and petty men’s appetites get whetted. Small minds and smaller men invariably fail to get on top of the chaotic situation. Yet, societies — especially those which take pride in being a nation of laws and constitutions — cannot live forever with chaos and violence; sooner or later, a need is felt, and felt keenly, that the mess be cleared up. That is the time when unorthodox men get called up and are told that they need not feel encumbered with orthodox methods.

A KPS Gill gets tapped on the shoulder.

Such men are leaders, who motivate their men and officers to cast doubts and diffidence aside; they take offence and have no qualms in giving offence; they have clarity and conviction; they achieve success and their goals by unconventional methods and unrestrained mandates; and, they invariably end up thinking they can take liberties with the laws and men and women (including a Rupan Deol Bajaj). Such men inevitably get tagged with a “controversial” dhobi-mark. Gill sahib was no exception.

Violence takes its own toll on society and on its moral and spiritual bearings — neither the victims nor the victors escape the brutalising consequences of violence; Punjab is still paying the price for those years of militancy, misguided and misled. Even after two decades of peace, small men have pushed themselves to the podium, they control the pulpit and would not allow fault-lines to be repaired. It is never a happy augury in a democracy when a man in uniform gets put on a pedestal, but let there be no mistake: If Punjab has known peace it is because out there was a man called KPS Gill.

******

I am not sure if very many people recall the shadowy figure of a so-called “godman” Chandraswami. Here was a man who, not long ago, could command respect and attention from heads of many governments and who could create headlines on his own — but he passed away in total obscurity, consigned to the back pages.

At one time, this tantric guru, an unattractive figure, was capable of making quite a bit of difference in our national politics. He had a strange hold over PV Narasimha Rao, one of the most educated and experienced men in our national life; and, his hold seemingly became stronger after Rao saheb got elevated as the prime minister. Besides Rao saheb, Chandraswami could count very many powerful leaders, across the political divide, among his bhakts.

I met him only once, that too at his insistence. That was a time when I used to report and write on the Congress Party and he wanted to understand from me “what was happening in the party.” This was after Rao saheb had ceased to be the Congress President. Chandraswami came across as oily and uncouth. But I do remember two important individuals — one, the influential head of a very huge private hospital in South Delhi and the other, a retired bureaucrat — being made to wait in the anteroom. My only thought after the meeting was: what could our leaders see in this man?

But they did eat out of his hand. As a “sant”, he could straddle the worlds of politics and religion. His religious garb liberated him from political or ideological ties; he had access to almost every Indian political leader of some consequence. But it still remains a mystery as to why a Sultan of Brunei or a Prime Minister of England or an international arms dealer like Adnan Khashoggi would come under the spell of this “swami”. How could this vastly uneducated man mediate and broker deals between powerful businessmen in London?

I believe that he was providing an often essential — but generally unacknowledged — service: the need for powerful figures — in business, politics, crime, finance — to try to get things moving outside the realm of what is permissible under the law and its procedures. Connections and contacts have to be made among legal, quasi-legal and plainly illegal entities and individuals to see to it that things do not get stuck; and, even though every State has its “agencies” to undertake unconventional chores, there are limits to how much a ruler can trust his own “agencies”. Secret envoys, middlemen, power-brokers — like Chandraswami —get pressed into service.

******

What do John D Rockefeller, Robert Clive, Genghis Khan, Margaret Thatcher and Deng Xiaoping have in common? They were all globalists, according to Jeffrey E. Garten, who in a new book, From Silk to Silicon argues that globalisation is a phenomenon that has been in the making for nine centuries, at least; and, nor is it going to go away in any great hurry — notwithstanding Donald Trump and other populist protectionists.

Besides these five, Garten writes about five others: Prince Henry (the explorer), Mayer Amschel Rothschild (the godfather of global banking), Cyrus Field (the tycoon who wired the Atlantic), Jean Monnet (the diplomat who reinvented Europe) and Andrew Grove (the man behind the Third Industrial Revolution). Through these lives, the spluttering story of globalisation is told, rather engagingly.

The connection between these lives is a bit of a stretch and the argument rather oversimplified. Yet, the basic outlines of the globalisation process do appear through these ten lives — at some point, a leader or an inventor or an empire builder or a banker has the imagination and the courage to move out of his familiar territory and to initiate new physical, commercial and cultural linkages.

Garten’s Ten were doers and movers, not great thinkers; they did not set out to be path blazers; but each one of them undertook enterprises which involved “long-term efforts” and “long-term horizons.” They turned out, according to Garten, “accidental globalists” insofar as they achieved transformative results which changed the ways the world did its business.

Garten is also careful to suggest that globalisation is not — cannot be — a pretty affair. Each of these ten priests of globalisation initiated changes that caused dislocation and destruction which, in turn, paved the way for peace, modernisation and prosperity. But after each round of dislocation and disruption, the rules of a new game would emerge because societies crave for order, predictability, regularity and hierarchy. The merit of Garten’s book is that each one of the ten chapters can be read in isolation, yet there is a kind of commonality in the manner in which change was brought about: “Taking advantage of shifting circumstances, identifying a major problem, attacking it at its weakest point with a clear strategic thinking and single-minded tenacity.” It involved marshalling resources, men and talent beyond national boundaries, inspiring and motivating followers to explore new territories and new ideas. Mercifully, Garten has included only those who he thinks made a “positive” contribution to the global well-being. Otherwise, Adolph Hitler, or Osama bin Laden would have also made it to the list.

******

Thanks to a new, strong and decisive government in Delhi, we all feel emboldened to rewrite history. Or, at least correct the distortions. Thanks to authoritative voices in the social media, we now learn that the first man to set foot on the Moon was none other than our very own Bahubali. But, due to the Cold War political pressure, NASA translated his name to Armstrong.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login